Realism 1830 - 1880

Until the end of the 19th century the term realism meant naturalism, or the representation of the external world as it is actually seen. Such an approach stressed actual experience as opposed to suggestive expression through metaphor or abstraction.

As a response to the political and social upheaval in Europe in the early part of the century, the Realists rejected the prevailing notions of academic and romantic art. Instead they presented a nonescapist, democratic, empirical investigation of life as it existed around them.

They painted ordinary people leading their everyday lives. Although other artists had depicted similar subjects in earlier times, the realists took a fresh and unemotional view. Realists conscientiously reproduced ignored aspects of contemporary life and society - its mental attitudes, physical settings, and material conditions of the middle and lower classes, the unexceptional, the ordinary, the humble, and the unadorned.

The perceived artificiality of both Classicism and Romanticism in the academic art was rejected. In France it was expressed as a taste for democracy and demonstrated the increasingly powerful interests of the bourgeoisie who were becoming concerned with both the factual and scientific verifiable.

Camille Corot River with a Distant Tower 1865

Realist pictures of working men and women going about their business could be distinctly ordinary. Many viewers criticised such pictures as lacking in poetry and imagination, while other critics applauded them as having a more democratic form of art in keeping with the times.

Some artists saw painting landscapes as a sympathetic gesture to those who have been forced away from nature to work in towns and cities as a result of the Industrial Revolution. The natural world was seen as a place of worship by poets and artists alike.

Although realistic paintings are not characterised by a single style, they offered infused with a robustness and energy conveyed through bold lines, strong tonal contrasts, broad handling of paint and a sombre palette.

You'll see from some of the artists listed below that there was a variety of representations of Realism. Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, for example, was interested in faithfully reproducing heroic scenes, such as major battles, in minute detail. He also had a particular interest in both the 17th and 18th Centuries, so many of his genre paintings were of people from that time.

Théodore Rousseau was regarded as a pioneer and a leader of the Barbizon School of landscape art. He was one of earliest artists to observe and analyze natural forms outdoors. He spent most of his career pursuing the portrayal of the French landscape.

Gustave Courbet, could be considered as an avant garde painter, who wanted to represent ordinary people living ordinary lives, without the sense of the heroic or of romanticism. As might be expected, this approach led to a great deal of criticism, as it was not considered 'high art'.

Jean François Millet also sought to represent rural life and rural workers, but can be viewed as making more of a political or social comment about the injustice towards the poor at the time.

Although Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot painted a number of portraits, he is largely remembered for his landscapes. He was particularly influenced by the realist Barbizon School in France which had a strong focus on tonal qualities, colour, loose brushwork, and softness of form. You can see how his style may have influenced the Impressionists who followed.

online Modern Art appreciation program

online Modern Art appreciation course

Realist art can be identified by the following features:

-

Scenes are from contemporary life, although religious subjects and landscapes often appear;

-

The theme is often didactic and intended to teach about the ills of contemporary society;

-

Works are easy to understand with honesty and sincerity towards the subject being highly valued;

-

The face-on point of view further reflects honesty;

-

Colour palettes are often drab with earthy tones and the application of paint is flat;

-

Baroque style drama is absent.

Artists from this period include:

-

Bonheur, Rosa 1822-1899

-

Boudin, Eugène 1824 - 1898

-

Castiglione, Giuseppe 1829-1908

-

Corot, Jean-Baptiste Camille 1796-1875

-

Courbet, Gustave 1818-1877

-

Daubigny, Charles-Francois 1817-1878

-

Daumier, Honore 1808-78

-

Gérôme, Jean-Leon 1824-1904

-

Klinger, Max 1857-1920

-

Lenbach, Franz 1836-1904

-

Menzel, Adolph 1815-1905

-

Meissonier, Jean-Louis Ernest 1815-91

-

Millet, Jean-François 1814-1875

-

Moreau, Gustave 1826-1898

-

Rodin, Auguste 1840-1917

-

Rousseau, Theodore 1812-1867

-

Virginie Demont-Breton 1859 - 1935

Key Realist Artists

Gustave le Gray, Tree Study, Forest of Fontainebleau, c1850

Gustave le Gray, Fontainebleau, chemin Sablonneuz Montant, c1850

Gustave le Gray, Oak Tree and Rocks, Forest of Fontainebleau, c1850

Theodore Rousseau, A Rockie Landscape, c1836

The Barbizon School and the Fontainebleau Forest

Once the domain and hunting ground of kings, the Forest of Fontainebleau became an important destination for many landscape artists from about the 1830s. During the 1820s and 1830s, painters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau helped to transform the nearby village of Barbizon into an informal artists’ colony and the forest into an open-air studio.

Only 40 miles southeast of Paris, the forest was a place of extraordinary beauty.

Through their close observation of the native countryside, these artists sparked a movement known as the Barbizon School that introduced a new sense of naturalism into landscape painting and challenged the French Royal Academy’s preference for idealised pastoral visions of nature.

In the 1830s landscape painting as a naturalistic representation was not an officially recognised art form - historical paintings in a landscape setting were fashionable, but direct studies from nature were not, which made it difficult for many of the artists to have their landscapes shown a the Salon.

However, the French Academy did have major role to play in encouraging artists to paint at Fontainebleau.

In 1816, the Academy introduced a Prix de Rome in Paysage Historique, historical landscape painting. The prize, awarded every four years, enabled its laureate to live and work at the Villa Medici in Rome, an opportunity conferred on promising French painters schooled in the academic canon. Intended to restore history painting to its seventeenth-century glory, the new Prix de Rome prompted a frenzy of excitement over landscape painting.

At the time, young artists were flocking to the Louvre to study seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish landscapes, a naturalist tradition long practiced in the Netherlands.

The exhibition of John Constable’s pictures at the Paris Salon of 1824 further set the stage for this new genre in France. In warm weather, artists now ventured outside Paris to work from nature, traveling to the royal parks of Saint-Cloud and Versailles and to more far-flung areas of the country - and no destination was more popular than the Forest of Fontainebleau which became a sanctuary for the growing leisure classes, for whom a train ride from Paris was an easy jaunt. (Source: https://www.galerie-dorsay.com/barbizonschool)

The Barbizon 'School' played a major role in establishing naturalism in French landscape painting. Many of the artists began to paint en plein air and thanks to technical developments in paint manufacturing, there was no longer any need to mix up pigments in the studio — they could just take their paint with them.

Camille Corot, Scene on the Saone River at Macon, 1834

French artist Gustave Courbet was perhaps the strongest exponent of the realist movement in the mid 1800s. Much like Caravaggio in the seventeenth century, he violated rules of artistic propriety by exposing the conditions of every day workers to the viewer.

His groundbreaking works portrayed ordinary people from the artist's native region on a monumental scale formerly reserved for the elevating themes of history painting. At the time, Courbet's choice of contemporary subject matter and his flouting of artistic convention was interpreted by some as an anti-authoritarian political threat. Proudhon, a French politician, the founder of Mutualist philosophy, an economist and a libertarian socialist, saw The Stonebreakers as an "irony directed against our industrialized civilization ... which is incapable of freeing man from the heaviest, most difficult, most unpleasant tasks, the eternal lot of the poor."

To achieve an honest and straightforward depiction of rural life, Courbet rejected the idealized academic technique and employed a deliberately simple style, rooted in popular imagery, which seemed crude to many critics of the day. His Young Women from the Village (see in the slideshow above), exhibited at the Salon of 1852, violated conventional rules of scale and perspective and challenged traditional class distinctions by underlining the close connections between the young women (the artist's sisters), who represented the emerging rural middle class, and the poor cowherd who accepted their charity.

The Stonebreakers (1850) was painted only one year after Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote their influential pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto' Inspired by the "complete expression of human misery" in an encounter with two road workers, Courbet asked them to pose for him in his studio. Painting the road workers life size on a large canvas, Courbet showed them absorbed in their task, faceless and anonymous, dulled by the relentless, numbingly repetitive task of breaking stone to build a road. It was considered to be scandalous.

When two of Courbet's major works (A Burial at Ornans and The Painter's Studio) were rejected by the jury of the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris, he withdrew his 11 accepted submissions and displayed his paintings privately in his Pavillon du Réalisme, not far from the official international exhibition.

Jean François Millet (1814-1875) was born into a peasant family near Cherbourg, in Normandy, France. His artistic talent was soon recognised, and after some training with local artists, the city of Cherbourg provided money for him to study in Paris. He spent some time in the studio of Paul Delaroche, and at the École des Beaux-Arts, and began his career as a portrait painter. In 1849, he moved to Barbizon, a small village in the Forest of Fontainebleau, just outside Paris, and began the series of rural scenes for which he became famous. The Sower, The Gleaners, and The Angelus depict local peasants, with a powerful simplicity and dignity.

His peasant background clearly left its mark as his paintings often reflect French rural scenes of the mid 1800’s. His art, though, does not portray an idyllic life. Millet’s theme consistently focuses on the ordinary and the actual.

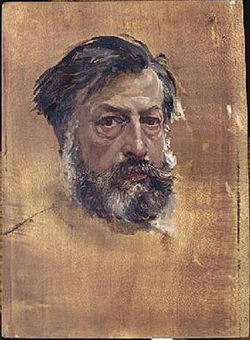

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796 - 1875) was a French landscape painter and Portrait painter as well as a printmaker in etching. Corot was the leading painter of the Barbizon school of France in the mid-nineteenth century. He is a pivotal figure in landscape painting which anticipates the plein-air innovations of Impressionism.

Between 1825 and 1843 Corot travelled to Italy, which was considered at the time to be essential to the formation of a landscape artist.

His reputation was established by the 1850s, which was also the period when his style became softer and his colours more restricted. In his late studio landscapes, which often included bathers, and allegorical figures, he used only a small range of colours, often using soft greys and blue-greens, with spots of brighter colour confined to the clothing of the figures. He preferred to focus on mood and atmosphere rather than topographical detail, particularly in what he called his ‘souvenirs’, which were based on memories of real landscapes.

Theodore Rousseau (1812-1867), together with Corot, is considered a to be founding members of the Barbizon movement. Their work had many similarities in subject matter and style, especially their manner of composing a picture through values. However, his work was considered a bold departure from the classical formulas of landscape painting and in particular, his early work was strongly criticised as being too ‘harsh’ and ‘boldly coloured.’ He was known amongst his fellow painters in Barbizon for his remarkable dedication to studying nature. A contemporary admirer said, “Rousseau was indefatigable in his analysis of nature. He observed, studied, sought for vulnerable points, and then painted. His results taught him new lessons, and he returned to nature to find out new secrets.”

As an exponent of realism, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891) is known primarily for his genre pictures and scenes of contemporary life. With his street views painted during the 1848 revolution and Napoleonic battle scenes, he is regarded as an accurate chronicler of his times, but Meissonier also had a fondness for the past, in particular for the 17th and 18th centuries. This tendency is also apparent in this painting of a young man busy writing (Young Man Writing, 1852) in the slideshow above. Although creating the illusion of a real, freshly observed situation, Meissonier has actually composed the scene carefully using various props. The large armchair covered in red fabric on which the man is sitting is in the style of Louis XIII (1601–1643). The sitter’s clothing, on the other hand, was in vogue during the time of Louis XVI (1754–1793). The style of painting is also inspired by the Baroque realism of the 17th-century Dutch masters, whose work Meissonier copied in the Louvre after his arrival in Paris as a young painting student.

Painter of animals (animalier), Rosa Bonheur was not only the first woman artist to be awarded the Legion d'Honneur, which was established by Napoleon I to honour the most accomplished citizens, she was also one of the most prominent women artists in Europe at the time. She didn't sentimentalise her subjects, but portrayed them in their natural habitat. She was both precise and painstaking in her technique - which evoked a strong sense of rural life.

Jean-François Millet, The Gleaners, 1857

The Gleaners is one of Millet's best known works, and we can tell it's a realist painting because there is a wonderful photograph from the 1800s which shows us a similar scene.

True to one of his favourite subjects – peasant life – this painting is the culmination of ten years of research on the theme of the gleaners. These women represent the rural working-class.

They were authorised to go quickly through the fields at sunset to pick up, one by one, the ears of corn missed by the harvesters.

Millet shows three women in the foreground, their eyes raking the ground. He demonstrates the three phases of the back-breaking repetitive movement imposed by this thankless task: bending over, picking up the ears of corn and straightening up again. We can see the sweeping movement of the action by the way in which the women are positioned.

Their austerity contrasts with the abundant harvest in the distance: haystacks, sheaves of wheat, a cart and a busy crowd of harvesters. The festive, brightly lit bustle is further distanced by the abrupt change of scale.

The slanting light of the setting sun accentuates the volumes in the foreground and gives the gleaners a sculptural look. It picks out their hands, necks, shoulders and backs and brightens the colours of their clothing. You can tell that these are work-roughened hands, and almost feel the aches in their backs from stooping.

Then Millet slowly smudges the distance into a powdery golden haze, accentuating the countryside in the background.

The man on horseback, isolated on the right (not easily seen), is probably a steward. In charge of supervising the work on the estate, he also makes sure that the gleaners respect the rules governing their task. His presence adds social distance by bringing a reminder of the landlords he represents.

There is a very limited palette in this painting. Note the use of graduated tones, with the use of blue and red in the caps of the women on the left to give them individuality, even though we can't see their faces. Our eye is also drawn through the centre of the work by the light in the woman's shoulder through to the background. However, they dominate the scene and their presence is powerful, even though in reality this was not the case.

Using simple pictorial composition, Millet gives these certainly poor but no less dignified gleaners recognition for the way in which they lived.

(primary source: http://www.musee-orsay.fr/index.php?id=851&L=1&tx_commentaire_pi1[showUid]=341)

Suggested Videos & Reading

Gustave Courbet, The Stonebreakers, 1849

Unlike Millet, who was known for depicting more idealised, hale and hearty rural workers, in The Stone Breakers, Gustave Courbet depicted road menders who wear ripped and tattered clothing. But this is not meant to be heroic: it is meant to be an accurate account of the abuse and deprivation that was a common feature of mid-century French rural life.

Courbet wanted to show what is “real” and in this monumental painting (it was 1.65 m x 2.57 m) he painted a scene he had actually witnessed: two men breaking stones beside the road.

He told his friends the art critic Francis Wey and Champfleury: “It is not often that one encounters so complete an expression of poverty and so, right then and there I got the idea for a painting. I told them to come to my studio the next morning.”

The two faceless stone breakers in Courbet’s painting are set against a low hill common in the rural French town of Ornan, where the artist had been raised and continued to spend much of his time. He used the difference in their ages to symbolise the cycle of poverty. The boy seems still too young for such back-breaking labours as he struggles with the heavy basket of gravel, whilst the much older man has dropped to his knees to wield his hammer on the rocks.

Courbet has ‘cast light’ on the plight of the labourers by placing them in strong light across the foreground of the painting, with the shadow of the hills behind them and only a small patch of blue in the upper right. But see how our eye is then drawn from the patch of sky down through the long hammer into the blue/grey of the cooking pot, then some small rocks and through to the blue socks of the labourer and up to the two figures. We are back to the central subject of the work – they dominate the work no matter where we look.

Like Millet, Courbet has used a very limited palette – it is only the small amount of the blue/grey and orange which bring relief from the muted earthy colours.

Unfortunately The Stonebreakers was a casualty of war: it was destroyed during World War II, along with 154 other pictures, when a transport vehicle moving the pictures to the castle of Königstein near Dresden was bombed by Allied forces in February 1945.

Suggested Videos & Reading

In 1855 Courbet wrote a Realist manifesto, echoing the tone of the period's political manifestos, in which he asserts his goal as an artist "to translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my epoch according to my own estimation." He stated in 1861 that "painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist in the representation of real and existing things".

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Camille Corot grew up in a middle-class family in Rouen, France, where he was a draper’s apprentice. From the age of 26 he pursued a career as an artist, taking painting lessons from A.E. Michallon and Victor Bertin, who ran a school for landscape painting.

In the autumn of 1825 Corot travelled to Rome to study the masters of the Italian Renaissance, but spent most of his time around Rome and in the Italian countryside. He considered that the three years that he spent in Italy were the most influential of his life, and he returned in 1834 and 1843.

Back in France, Corot constantly travelled in the warmer months, sketching and making preparatory studies, before returning to his studio to paint in winter.

He approached his landscapes in a traditional manner. His palette was restrained and dominated by browns and blacks, together with dark and silvery green. Although at times his brushstrokes appeared to be rapid and spontaneous, they were usually controlled and careful. His compositions were well planned and generally rendered as simply and concisely as possible, heightening the poetic effect of the imagery. As he stated, “I noticed that everything that was done correctly on the first attempt was more true, and the forms more beautiful.” With an instinctive sense of arrangement, and drawing on the lessons of his former teachers, Corot gave his works a seemingly natural harmony and balance, responding to the light and atmosphere of the views he painted.

From 1831 he held regular and successful exhibitions in Paris. He understood that to be noticed on the crowded walls of the Salon he needed to work on an impressive scale and include interesting subject matter into his foregrounds. Using his sketches and studies from Italy and around Barbizon near the Fontainebleau Forest he composed landscapes of increasingly large size, enlivening their foregrounds with rustic genre motifs. His first success came at the Salon of 1833, where his Vue de la forêt de Fontainebleau won a silver medal.

From the 1850s Corot’s style drew greater admiration from his fellow artists. His work from this time on fell into three main categories: private studies from nature of landscape or of the human figure; more academic historical compositions destined for the Salon; and composed landscapes in hazily atmospheric settings destined for sale – for which there developed a strong demand. He called these landscape souvenirs and paysages, dreamy imagined paintings of remembered locations from earlier visits painted with lightly and loosely dabbed strokes. It is these works in particular which have endured as a legacy.

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier is best known for painting miniatures in oils, with scrupulous attention to detail. He specialised in scenes of bourgeois domestic life from the 17th and 18th centuries, portraying his subjects playing chess, smoking pipes, reading books, sitting near musical instruments, or posing in the uniforms of musketeers.

He had only a brief artistic education and was largely self-taught, carefully studying the Dutch, Flemish and French painters at the Louvre.

His first submission to the Paris Salon, before he turned 20, was in 1834. Flemish Burghers, 1833-4 was a small costume piece featuring three gentlemen clad in traditional 17th century clothing. Following the success of this painting at the Salon, Meissonier painted numerous paintings in a similar style and became the most sought-after painter of the decade, appealing to a wide range of collectors.

However, during the 1848 revolution in Paris, as a captain in the National Guard, Meissonier led the troops responsible for defending the Hôtel de Ville. It was here he witnessed the carnage of the battle first hand and in response he painted one of his most significant images: Memory of the Civil War (The Barricades). Unlike Delacroix's romantic painting, Liberty Leading the People, painted at around the same time, this was an unflinching depiction of the incomprehensible horror of civil war. Piles of bodies lie in the street in varying stages of decomposition. Blue and white shirts, stained with blood, create a grim “tricolour”. The painting received a great deal of attention when it was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1850-51 (known locally as the “Realist Salon” as there were so many realist paintings).

It was from about this time that he also painted large military and historical scenes, including such works as Friedland, 1807. Meissonier worked with elaborate care and scrupulous observation, and some of his works took up to 10 years to complete.

In 1889 he accepted the position of president of the Exposition Universelle, France’s extravaganza celebration of the centennial of the Revolution - for which the Eiffel Tower was designed. He exhibited 19 paintings at the Expo and became the first artist to be awarded the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour. Unflagging in his commitment to the arts, he also helped to establish the independent Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts the following year, and became its first president for a brief period prior to his death in 1891.

Suggested Videos and Reading

Corot to Monet | Exhibitions | The National Gallery, London

Rosa Bonheur

Born in Bordeaux in 1852, Rosa Bonheur was trained by her father, a drawing instructor and landscape painter, and also copied art at the Louvre.

Her primary interest was painting animals, and she was allowed to bring animals into the family studio so she could study them, and later went to a slaughter house in Roule to study animal anatomy.

Bonheur made her debut at the Paris Salon in 1841 with two paintings, including Rabbits Nibbling Carrots. By 1845 she was being awarded medals by the Salon jury, and in 1849 exhibited Ploughing at Nivernais, which has been commissioned by the government of the Second Republic. It was greatly welcomed by government officials, critics and viewers as it strongly evoked rural productivity.

In 1851, she undertook twice weekly visits to the Paris Horse market in preparation for another ambitious work, The Horse Fair. After the painting was exhibited at the Salon in 1853 Bonheur was awarded hors concours status and granted the privilege of exhibiting whatever she wished at future Salons (at that time this privilege was reserved for members of the Légion d'Honneur and Academie des Beaux-Arts.

The Horse Fair was purchased by a British gallery owner and art dealer, Ernest Gambart, who invited her to Britain to meet the President of the Royal Academy, John Ruskin and Britain's foremost animal painter (animalier), Edwin Landseer, whom Bonheur greatly admired.

At this time she was introduced to new animals and new subjects and in 1856 she painted Gathering for the Hunt, combining horses, dogs and riders in the early morning countryside. (Given her success with The Horse Fair its not surprising that she chose to follow up with other compositions featuring horses, and hunting scenes were a suitable and traditional choice.)

Because of her success in Britain and the USA, her dealers were able to sell most of her work to collectors so she felt little need to participate in exhibitions in France, although she did participate in both the 1855 and 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

In the 1890s she occasionally participated in exhibitions of the Union of Femmes Peintre et Sculpteurs and was named honorary life President.

The Horse Fair, 1853

Before the 1853 exhibition of The Horse Fair, Bonheur's reputation as an animal painter, which was already considerable, rested on her depictions of farm animals. Although she had exhibited several paintings of horses in the 1840s, it was The Horse Fair that firmly established her as a competent equine painter. In this painting the rearing and lunging horses surges past as the grooms struggle to control them.

It has been suggested that the rider in the blue cap in the centre of the painting may be a self portrait that Bonheur included as a way of publicly questioning and resisting conventional female roles. By the time she started work on this painting she had adopted a more masculine form of dress (possibly for practical reasons as she worked closely with animals) which became habitual costume for her - but she had to obtain to police permission to wear trousers and loose blouse in public!

Bonheur is considered a Realist as she did not sentimentalise her subjects, but portrayed them in their natural habitat. She collected a number of animals on her estate, at By, near the forest of Fontainebleau, including deer, horses, dogs and lions, which by the 1870s became the subject of both oil paintings and watercolours.

In later years she became interested in buffaloes after Buffalo Bill Cody brought his wild west show to Paris for the Exposition Universelle of 1889.

Source: Susan Waller; Bonheur, Rosa, in Dictionary of Women Artists, Vol 1, Gaze Delia (ed) Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, Chicago, 1997

Create an artwork, using any media, to express hardship in today's everday life. Use only muted tones. How much of a sense of realism can you express? What is the effect of using a limited palette?