Cubism 1908 - 1922

Cubist painters re-examined and challenged the concept that art should copy nature, and also challenged the traditional techniques of perspective, modeling and foreshortening.

In cubist works the artists combined a large range of viewpoints (multiple perspectives) in one picture and broke down the natural forms of subjects into geometric shapes.

This style of painting was largely influenced by Paul Cezanne, following a commemorative exhibition of his work in Paris in 1907. In particular, the exhibition demonstrated Cezanne's

-

use of geometric shapes,

-

build-up of small brushstrokes,

-

flattened perspective, and

-

way of viewing his subject from shifting positions.

You'll also see that early cubist works contained similar colours to Cezanne, that is beige, creams, greys, black and browns.

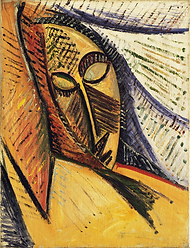

Another key influence was African art, with its vibrant expressive qualities and simplification of forms as planes or facets. A number of cubist artists purchased African tribal masks, which were common and cheap in Paris curio shops. However, they were not interested in the true religious or social symbolism of these cultural objects, but valued them for their expressive style. Similarly, artists were also influenced by Iberian sculpture.

The birth of Cubism is attributed to Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, who collaborated closely for some years from 1907, after being introduced by Art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who promoted Cubism from its inception. They were joined by a number of other artists from about 1910, including Fernand Léger, Sonia Delaunay and Juan Gris.

In 1908, Henri Matisse labelled Braque's work "les petites cubes," leading the critic Louis Vauxcelles to coin the term Cubism.

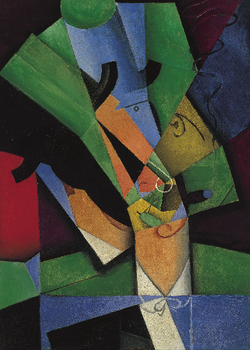

Georges Braque, Violin and Candlestick, 1910

Cézanne was my one and only master! I spent years studying [his pictures] ... Cézanne! It was the same with all of us – he was like our father.

- Pablo Picasso

Georges Braque, Viaduct at L'Estaque 1908

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Sleeping Woman, 1907

Picasso would have seen 9th century

sculpture similar in style to this in Paris

Paul Cézanne The Bibémus Quarry c. 1895

Cubist art can be identified by the following features:

-

Geometric shapes;

-

Multiple viewpoints

-

Influence of African masks and Iberian sculpture;

-

Monochromatic colours in early phase;

-

Every day subject matter;

-

Collage, Papier Collé and Assemblage.

Artists from this period include:

-

Georges Braque 1882 - 1963

-

Pablo Picasso 1885 - 1973

-

Albert Gleizes 1881 - 1953

-

Jean Metzinger 1883 -1956

-

Sonia Delauney 1885 - 1979

-

Robert Delaunay 1885 -1941

-

Fernand Léger 1881 - 1955

-

Juan Gris 1887 - 1921

-

Marie Laurencin 1883 - 1956

-

Marie Vorobieff (Marevna) 1892 –1984

Key Cubist Artists

Pablo Picasso - Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon marked a radical break from traditional composition and perspective in painting, and Picasso chose not to exhibit it publicly for some years (in 1916) after he painted it in 1907. The painting is considered to be a fore-runner to Cubism.

It's a large work which appears square (in reality there are a few centimetres more to its height than its width). It took nine months to complete, and Picasso created hundreds of sketches and studies in preparation for the final work.

The Avignon of the work’s title is a reference to a street in Barcelona famed for its brothel, and Picasso started out with the idea of a brothel scene. In its early forms the painting was to have a male customer in it - a medical student or a sailor. It would have been a slice of contemporary Parisian life, not that far removed from other painters of modern life at about that time.

However, this is a painting of nudes in which there are almost no curves to be seen - elbows sharp as knives, hips and waists geometrical silhouettes, triangle breasts - which is why it has cubist links.

The finished painting depicts five naked prostitutes; two of them push aside curtains around the space where the other women strike seductive and erotic poses—but their figures are composed of flat, splintered planes rather than rounded volumes, their eyes are lopsided or staring or asymmetrical, and the two women at the right have threatening masks for heads. The space, too, which should recede, comes forward in jagged shards, like broken glass.

In the still life at the bottom, a piece of melon slices the air like a scythe denoting a sexual reference.

Looking at the picture means moving constantly from one facet to another; it never lets you settle on one resolved perception. All of the women demand attention and like Manet's prostitute Olympia, the central prostitutes stare directly at the viewer.

Picasso also introduced African masks for the women on the right, which combined with the colours, composition, flattened perspective and angular shapes made this a very modern work which invites you to your own interpretation of its meaning. Art historians have found attached different meanings to various symbols in the painting.

online Modern Art appreciation program

online Modern Art appreciation course

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suggested Videos and Reading

Smarthistory documentary video about this painting

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fy2TlYnYIzA&index=31&list=PLkVVQty3LEWNBkv_5OodsfMOsupP8rPyo

Guardian article http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2007/jan/09/2

Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso - The beginnings of Cubism

In 1908, Braque completed a number of landscapes in the French fishing village of L'Estaque that reduced everything to geometric patterns, (or cubes, according to Matisse). By this time, Picasso had already finished his painting Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) which also incorporated the use of geometry, as well as African art.

The two artists began working together in 1909, spending much time together talking about, as much as painting, this new style of art. It is clear that they were enjoying experimenting with geometry, perspective, and representing three dimensions in a two dimensional space (the canvas). They wanted to introduce the idea of 'relativity' - how the artist perceives and selects elements from the subject, fusing both their observations and memories into the one concentrated image. To do this they spent some time considering the way that people actually see.

They felt that when you look at an object your eye scans it, stopping to register certain details before moving on to the next point of interest, and so on. A viewer can also change their viewpoint in relation to an object by looking at it from above, below or from the side. As a result they proposed that 'seeing' an object is the sum of many different viewpoints, and your memory of an object is constructed from many angles depending on your line of sight and your movement. For Braque and Picasso the whole idea of space was reconfigured: the front, back and sides of the subject become interchangeable elements in the design of the work.

They began to fracture (break up) the objects they were painting into a large number of sharp-angled shapes, known as facets, all painted from different perspectives. During 1909 - 1911 their multi perspectives became more radical. The facets were drawn from different angles, and often appeared to overlap. The result could be somewhat like a jigsaw puzzle, with the pieces deliberately mixed up, so that they viewer has some clues as to what they were seeing, but could interpret different sections of an artwork differently.

Both Braque and Picasso helped the viewer with their interpretation by generally using traditional and neutral subjects (often musical instruments, bottles, pitchers, glasses, newspapers, playing cards, and the human face and figure), but often a line or shape could be seen to perhaps be several different things, or facing in different directions.

Because the artists deliberately wanted to avoid the expressive nature of colour, they used a monochromatic palette (ochre, beige, black, and white). Often their work was so similar when they painted side by side it was difficult to tell who was the artist.

Braque and Picasso painted together until the first World War commenced in 1914. During the war Braque suffered a serious head wound and after he returned home his work became less angular and featured subtle muted colours and a more realistic interpretation of nature. At the same time, Picasso was also moving in new directions.

Cubist Styles

Cubism is generally divided into two stages.

Analytical Cubism - the early phase of cubism (from about 1908-12) is chiefly characterised by the pronounced use of geometric shapes, fragmentation, multiple viewpoints and monochromatic use of colour.

Paintings produced at this time were often more detailed than later cubist works, with images often gathered tightly toward the centre of the painting, growing sparser toward the edges. Although figures and objects were dissected or "analysed" into a multitude of small facets, these were then reassembled, after a fashion, to evoke those same figures or objects.

Synthetic cubism refers to the later cubist works (from about 1912-1922) in which the artists synthesised or combined forms, creating three new art techniques.

-

One was collage, using pre-existing materials or objects pasted (or otherwise adhered) to a two-dimensional surface. The artists used collage to further challenge the viewer’s understanding of reality and representation.

-

The second was papier collé, or cut-and-pasted paper including words, graphics and patterns, to achieve a desired thematic result.

-

The third is assemblage, or a three-dimensional collage. Assemblage was a major breakthrough in sculpture. For the first time in Western art, sculpture was not modelled in clay, cast in plaster and metal, or carved of stone or another material. This would pave the way for other artists to assemble found objects up to the present day.

During this period colours were much brighter, geometric forms were more distinct, and textures began to emerge with additives like sand, paper or gesso.

Analytic Cubism - Pablo Picasso Ma Jolie 1911 - 12

The name of this work, Ma Jolie, (My pretty girl) came from a popular song performed at a Parisian music hall. It was also Picasso's nickname for his lover Marcelle Humbert (also known as Eva Gouel).

He composed the figure into different planes, angles, lines, and shadings, completely abstracting the face.

Because of the limited palette in this painting, common to Analytic Cubism, deciphering the clues or elements is made more difficult. It could easily appear to be just geometric shapes and words with little meaning.

But you can see that Picasso was building an image made up of multiple facets which invite investigation.

You can also see that Picasso, and fellow artist Georges Braque, would have seen these early experiments in breaking down images as motivation to continue to push the boundaries in terms of painting construction and the use of colour - leading very quickly to what has become known as Synthetic Cubism.

Synthetic Cubism - Collage - Pablo Picasso, Still Life with Chair-Caning, 1912

During the summer of 1912, Braque left Paris to holiday in Provence. During his time there, he wandered into a hardware store, and found a roll of oil cloth printed with a fake wood grain (an early version of contact paper/vinyl adhesive with pre-printed patterns used to line drawers in a cupboard).

The particular pattern drew his attention because he working on a Cubist drawing of a guitar, and he was about to render the grain of the wood in pencil. Instead, he cut the oil cloth and pasted a piece of the factory-printed grain pattern onto his drawing. Before becoming an artist, Braque was involved in home decoration, and he brought these skills to his art.

About the same time, Picasso glued a piece of oilcloth printed with a tromp l'oeil chair-caning pattern to a small canvas, added other elements, and named it Still-life with Chair-caning. Picasso had affixed pre-existing objects to his canvases before, but this picture marks the first time he did so with such playful and emphatic intent. The chair caning in the picture also comes from a piece of printed oilcloth - and not, as the title suggests, an actual piece of chair caning. But the rope around the canvas is very real, and serves to evoke the carved border of a cafe table. Hence the picture not only dramatically contrasts visual and sculptural/tactile information, it also confuses our sense of what is horizontal and what is vertical.

Suggested Videos and Reading

video by smarthistory about this artwork

Papier Collé - Picasso, Man with a Hat and a Violin, 1912

Man with a Hat and a Violin is a Papier Collé made from cut and pasted newspaper and charcoal on two joined sheets of paper.

This work, created in Paris, belongs to a group of about seventeen other papiers collés by Picasso composed solely from newspaper articles. Here, he arranged cuttings from Le Journal of December 3 and 9, 1912 , on a sort of scaffolding of straight and slightly curved charcoal lines. The various texts refer to the Balkan Wars, the unrest of miners in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais départements, critical issues debated in Parliament and in the Chambers, and to local announcements and advertisements. (source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Assemblage - Picasso, Guitar 1912

Picasso crafted his Guitar and hung it on his studio walls sometimes as an individual object and at other times as part of larger still life compositions.

The body of the guitar has been folded onto itself in a shape that's similar to a box. The box is held together by sewn stitches. The components have been cut from pieces of cardboard or paper. These very basic materials make their way into the artist's palette.

One of the parts of this object that is seen as being most radical is the way that he created the sound hole. If you conjure in your mind a real guitar, the sound hole registers as a negative. But Picasso has cut away the front of his instrument and then created a cylinder from cardboard, to give something that is intangible a defined volume.

Picasso wasn't trained as a sculptor. There's a declared lack of interest in fine finish, or craftsmanship. The edges are a little jagged. The glue shows. The strings are imperfectly tied. It's not about making something perfect. That wasn't the intention. It's that Picasso can make this incredibly sort of magical, alluring object out of virtually nothing.

(source: Museum of Modern Art)

Suggested Videos and Reading

For more about Picasso's guitars you may be interested in this MoMA interactive:

http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2011/picassoguitars/index.php

Albert Gleizes, Man on a Balcony, 1912.

Man on a Balcony (also known as Portrait of Dr. Théo Morinaud and 'L'Homme au balcon) was exhibited in Paris at the Salon d'Automne of 1912. (The Cubist contribution to the salon created a controversy in the French Parliament about the use of public funds to provide the venue for such 'barbaric art'.)

In this painting, the man leaning nonchalantly against a balustrade occupies the foreground of the composition, gazing at the spectator. At first glance he appears bathed in natural light. But upon closer examination there is no clear light source or direction from which the light emanates, giving the overall work the theatrical feeling of a stage set.

The composition exemplifies the Cubist style of reverberating lines and fractured planes, applied to the traditional format of the full-length portraiture. The treatment of the subject is sufficiently representational to permit the identification of the tall, elegant figure as Dr. Théo Morinaud, a dental surgeon in Paris. While still 'readable' in the figurative or representational sense, Man on a Balcony demonstrates the mobile, dynamic fragmentation of form characteristic of Cubism at the artistic movements peak of 1912.

There is an interplay of perpendicular lines and hyperbolic arcs that produce a rhythm across the complex urban backdrop; such as smokestacks, train tracks, windows, bridge girders and clouds (the view from the balcony of the doctors office on the avenue de l'Opéra).

Highly sophisticated both physically and in theory, Gleizes has visualised and presented objects from several successive viewpoints. He deliberately contrasts angular and curved shapes, whilst using tubular, block-like forms for the figure and head.

The grey, ochre, beige and brown colours, often identified with Cubism, suggest the grimey, smokey city atmosphere, although Gleizes has enlivened this neutral palette by including bright greens and reds as well as cream highlights.

After the completion of both this work Gleizes became convinced that artists could explain themselves as well as or better than critics. In 1912 he and Jean Metzinger wrote Du "Cubisme", the first major text on Cubism. He wrote and granted interviews during the following years when Du "Cubisme" was enjoying wide circulation and considerable success.

Writing in The Epic, From immobile form to mobile form (first published in 1925), Gleizes explains the key to the relationship that develops between the artwork and the viewer, between representation or abstraction of form:

" The plastic results are determined by the technique. As we can see straightaway, it is not a matter of describing, nor is it a matter of abstracting from, anything that is external to itself. There is a concrete act that has to be realised, a reality to be produced - of the same order as that which everyone is prepared to recognise in music, at the lowest level of the esemplastic scale, and in architecture, at the highest. Like any natural, physical reality, painting, understood in this way, will touch anyone who knows how to enter into it, not through their opinions on something that exists independently of it, but through its own existence, through those inter-relations, constantly in movement, which enable us to transmit life itself."

source: Wikipedia

Using any media, create two cubist works. The first should be any earlier form using geometric shapes, and the second should be an assemblage.

Which one have you enjoyed more?

Suggested Videos and Reading

BBC documentary video about Picasso

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ANqi-LuH5j8

Santa Barabara Museum of Art Picasso and Braque's Cubist Experiment: "Like mountain climbers roped together"?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ju1HsOAtN8c