Symbolism 1880 - 1910

Symbolism was both an literary and artistic movement prominent in the last two decades of the 19th Century, when symbols were used to express the imagination of both poets and artists – with ‘dreaming’ being the essence of their creativity.

Musicians were also experimenting with innovative forms, emphasising subtlety, mood and imagination.

Symbolist origins in art can be traced back to the paintings of Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes were producing in the 1860s and 70s. Both artists were drawn to Romantic subjects and concepts that focused on emotion and allusion, and subjectivity over objectivity. While Moreau created theatrical compositions with richly decorative surfaces and great detail, Purvis de Chavannes produced monumental forms with muted colours in order to express abstract ideas. His style led to a preference for broad strokes of unmodulated colour and flat, often abstract forms by future Symbolist painters.

Moreau later said that he did not believe in what he could touch or in what he could see; the only things that he believed in were the things he could not see. *

Symbolist writers such as Gustave Kahn and Jean Moréas, and poets Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarme, had a significant influence on the development of the art style. At the age of 22 Mallarmé spoke of a new use of language which would “paint not the thing itself but the effect that it produces“. He considered that straight description had no place in art and “to name an object“, he wrote in 1891, “is to deprive the public of three quarters of its pleasure…. Guesswork should enter into it. To suggest – that should be the poet’s dream. In suggesting, he makes the best possible use of that mysterious thing, the symbol”. **

Jeanne Jacquemin, Daydream, 1894.

Paul Gauguin also played an important role in the development of Symbolism. By 1885 both his writing and his painting were reflecting Symbolist interests. He believed that the emotional response to nature was more important than the intellectual; that lines, colours and even numbers communicated meaning; intuition was crucial to artistic creation, and that artists should communicate ideas and feelings derived from nature by means of the simplest forms, after dreaming in front of the subject.

In 1891, in an article about Gauguin, Albert Aurier described Symbolism as " the subjective vision of an artist expressed through a simplified and non-naturalistic style" . ***

Symbolist artists painted in a highly metaphorical and suggestive manner, using subtle symbols which emphasised the meaning behind the forms, lines, shapes, and colours of their subject matter.

Many symbolists believed that art should reveal absolute truths and that these truths could only be found in either a spiritual or mystical realm, or as a result of personal experience, rather than an purely objective view of the material world. They emphasised depicting emotions which were difficult to visualise.

Rather than sharing a single artistic style, they believed that there should be more to art than was encompassed by everyday visual experience.

In 1889 Edvard Munch defined what he saw as the limitations of Impressionism, “I’ve had enough of ‘interiors’ and ‘people reading’, and ‘women knitting’, I want to paint real live people who breathe, feel, suffer and live. People who see these pictures will understand that these are sacred matters, and they will take off their hats, as if they were in church“. ****

The key themes in Symbolist art were love, fear, anguish, death, sexual awakening, and unrequited desire, with women often being the main symbol for expressing these themes, typically either as the virgin or femme fatale.

Inspiration often came from folk tales, biblical stories, Greek mythology, imaginary dream worlds and hallucinatory revelations (as the result of drug use).

Odilon Redon, another early Symbolist, worked almost exclusively in black and white until in his 50s, creating numerous subjects influenced by the writer Edgar Allan Poe. Later works were beautifully coloured.

It is no co-incidence that psychiatry and psychoanalysis were developing at exactly the same time – Sigmund Fraud’s probing into the unconscious and the meaning of dreams resonated with the Symbolists. There was also a general reawakening of interest in spirituality, in both the conventional church and unconventional esoteric cults. It was also a time when interest was developing in vegetarianism, mediation and naturism. *****

Other artists associated with Symbolism are James Ensor, Henri Rousseau, Gustav Klimt and Jeanne Jacquemin.

Of all the major movements of the second half of the 19th Century, Symbolism was the most pervasively European and least focused on France – it had followers in Britain, Belgium, Austria and Scandinavia.

* ** **** John Russell, The Meanings of Modern Art, Thames and Hudson, 1981, pp 72 – 74.

*** Herchel B Chip (ed), Theories of Modern Art, A Sourcebook for Artists and Critics, p89.

***** Symbolism, in The Illustrated Story of Art, Doring Kingersley, London, 2013, pp 298 – 307.

Symbolist art can be identified by the following features:

-

Mood rather than style;

-

Macabre imagery;

-

Orientalist subjects;

-

Female sensuality/death/violence/the supernatural;

-

Elaborate ornament;

-

Mythological subjects;

-

The most common themes in symbolist art include “love, fear, anguish, death, sexual awakening, and unrequited desire";

Artists from this period include:

-

Gustave Moreau 1826 - 1898

-

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes 1824 - 1898

-

James Ensor 1860 – 1949

-

Edvard Munch 1863 - 1944

-

Henri Rousseau 1844 -1910

-

Odilon Redon 1840 - 1916

-

Gustav Klimt 1862 - 1918

-

Jeanne Jacquemin 1863 - 1938

-

Romaine Brooks 1874 - 1970

Key Symbolist Artists

Gustave Moreau

Gustave Moreau is recognised as a founder of the Symbolist movement in France, although his paintings in this style began being exhibited some 15 years before the movement is considered to have commenced. His favourite subjects were ancient civilisations and mythological themes which he portrayed in densely worked, encrusted canvasses.

He was chiefly influenced by Romantic painters Eugene Delacroix and Theodore Chasseriau and their use of exotic romanticism, dramatic lighting and bright colours. After Chasseriau’s untimely death at the age of 37, Moreau undertook a two year study trip to Italy from 1857, where he studied Renaissance masters and became convinced of the spiritual value of art.

His travel through the towns and cities of Italy also exposed him to the influence of Byzantine enamels, early mosaics, and Persian and Indian miniatures, all of which played a significant role in the evolution of his individual style and in the jewel-like effect of his technique, noted Bennett Schiff in the Smithsonian in August 1999.

Like many other artists in Paris at the time, Moreau was also influenced by Asian art. In 1869, he attended the Palais de l’Industrie which was the largest and most extensive exhibition of Asian art held in Europe. It consisted of over 1,000 objects from China, Japan, India and Persia. Moreau sketched many of the works which were exhibited and incorporated the style of drawing into many of his works.

At the Paris Salon of 1864 Moreau exhibited his first major work, Oedipus and the Sphinx, which launched him into prominence. It established his lasting preoccupations with the opposition between good and evil, male and female and physicality and spirituality. To Moreau, the work represented humankind facing the eternal mystery of life with moral strength and self-confidence.

Schiff wrote that “Outstanding examples of psychological and physical detachment can be seen in one after another of Moreau’s paintings… In Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864), for instance, the winged creature – half nude female, half lion, an incubus clawed into Oedipus’ breast – does not seem to inflict pain at all. Instead, the grotesque creature and its placid victim appear to be dreamily engrossed in each other, although Oedipus is soon to answer the Sphinx’s riddle and she, or it, is to fall dead to the ground, finally, having already shredded any number of hapless voyagers unable to answer the riddle. Their bits and pieces are, in Moreau’s superbly rendered canvas, strewn about the foreground.”

In 1876 Moreau exhibited three of his most famous paintings in the Salon: Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra, Salome Dancing Before Herod, and The Apparition.

Gustave Moreau, Salome Dancing before Herod, 1874-76

Gustave Moreau, The Apparition, 1886

Gustave Moreau, Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra, 1875-6

The Apparition portrays Salome who, according to the Gospels, bewitched the ruler Herod Antipas, the husband of her mother Herodiad, with her dancing. As a reward she was given the head of John the Baptist.

Several influences can be seen in this composition, including his copies of Japanese prints from the Palais de l’Industrie.

There is also a reference to head of Medusa, brandished by Perseus, in Benvenuto Cellini’s bronze in Florence (Loggia dei Lanzi). The decoration of Herod’s palace is directly inspired by the Alhambra in Granada. Through these various elements, Moreau recreates a magnificent, idealised Orient, using complex technical means such as highlighting, grattage* and incisions.

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

“He didn’t set his pupils on the right road,” Matisse said. “He took them off it. He made them uneasy…. He didn’t show us how to paint; he roused our imagination.” quoted Hilary Spurling in The Unknown Matisse: A Life of Henri Matisse: The Early Years, 1869-1908.

*Grattage is a technique in which (usually wet) paint is scraped off the canvas.

Suggested Videos and Reading

Moreau:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtlGORJLTq4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AuhcnmLYCOs

(but please note the last video has references to homosexuality)

Puvis de Chavannes

Romaine Brooks

Edvard Munch

Gustave Klimt

Jeanne Jacquemin 1863 - 1938

Odilon Redon Self Portrait 1880

James Ensor, Self Portrait with a Flowered Hat 1883 - 88

Gustave Moreau

Henri Rousseau

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes - Symbolism and Hope

Pierre - Cécile Puvis was born at Lyon in France in 1824. (It was not until later in life that he added 'de Chevannes' to his surname, which originated from his aristocrat forebears in Burgundy.)

Whilst his contemporaries were Édouard Manet and realist Gustave Courbet, Puvis drew from Classicism in keeping with academic traditions of the Paris Salon. His subject matter was imbued with religious themes, allegories, mythologies and historical events. Nonetheless his interpretation of Classicism gave his work a modern, abstract look which not only appealed to symbolist writers and artists of the time, but also marked him as an avante-garde artist of the period.

Puvis' formal training during the late 1840s was limited to study trips to Italy and shortlived work in the studios of Henry Scheffer, Delacroix and Couture. He also found inspiration in Romantic artist Théodore Chassériau. Initially Puvis was most interested in painting grand, public paintings which be began exhibiting at the Paris Salon from 1859 onwards. (After achieving public recognition, he served on Salon juries.)

He was also interested in Commissions from the French government and is now mostly remembered for the huge canvases and murals he painted for the walls of city halls and other public buildings in Paris such as the Panthéon, the Sorbonne, and the Hôtel de Ville, as well as buildings in other parts of France.

His style developed from painting these large works, and he is known for simplified forms, flatness of the picture surface, rhythmic line, and the use of non-naturalistic and muted colours to evoke mood. As a result, the figures in his paintings seem to be wrapped in an aura of mystery, as though they belong in a private world of dreams or visions, which is why they are considered to be part of the symbolist style, although Puvis didn't identify himself as with Symbolist painter. Noneless, he was considered by a younger generation of artists, such as Gauguin, as a leader of the Symbolist movement.

Puvis was keenly in interested supporting a younger generation of artists and was a leading member, and one time President, of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, which aimed to create a Salon that was more selective, prestigious and noticeably more modern than the Paris Salon.

His style can be seen not only in works by Gauguin, but also in Picasso's paintings from his Pink and Blue period, works by Matisse such as The Joy of Life, 1906, and many other artists who followed.

Hope, 1972

Puvis was deeply affected by the Franco-Prussian war and Paris Commune (1870-71) and he produced several artworks related to the conflict and deprivation brought about as a result of the war.

In particular, in 1872 he exhibited Hope at the Salon (now in the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore). The Musée d'Orsay has a smaller version, also painted between 1871 and 1872.

In the larger painting, Puvis portrays Hope as a naked girl sitting on a burial mound covered with white drapery. Behind her, a desolate landscape with the ruins of a building and the makeshift crosses of improvised cemeteries evoke the recent war. Dark clouds can be seen in the distance, but are breaking up into a softer hue. Other elements in the painting point to a new era, full of promise. The olive branch in the young woman's hand symbolises the nation's recovery from war as does the new growth of flowers from the rocky outcrops, while the white in the dress/drapery suggest the return of lightness.

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

However, the lack of any historical detail gives the painting a universal sense of symbolism, so that it could apply to Hope in a variety of contexts. he simplified composition of the work, the use of matte colours and the sense of rhythm are very characteristic of his style.

Paul Gauguin had a reproduction of this painting in Tahiti and it figures in his Still Life with Hope, painted in 1901. As well, the subject in his painting Te Aa No Areois from 1892 is seated in a similar fashion to the model in Hope.

Puvis de Chavannes’s Hope was also the inspiration for two later works, painted after the first World War.

In 1923, Pablo Picasso painted Woman in White. In this painting, his 20th century post-war allegory of Hope is less obvious than in the painting by Puvis de Chavannes, as he omits the laurel branch and crosses, and the figure is in a more relaxed pose.

It’s been suggested by Kenneth Silver^ that Picasso presents his figure of hope as a general symbol of cultural endurance and women’s fertility (with maternité (motherhood) themes being popular with avante-garde painters at the time).

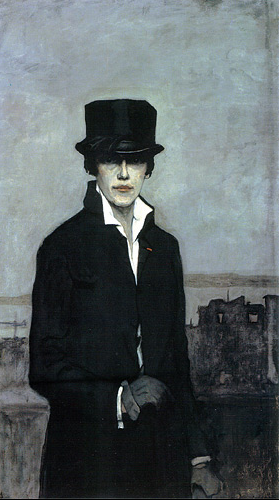

Romaine Brooks’s Self Portrait, painted in the same year as Picasso’s Woman in White, also appears to be a more modern take on Hope, with the foreground placement of a silhouetted woman towering over a distant landscape, the distinctive horizontals in the painting, the general atmospheric effects and the shape and placement of the large ruined building on the right. Brooks, however, most likely had a different theme in mind than either Puvis or Picasso. It is more likely that she was representing hope as a new set of post – war possibilities for women, beyond maternité.

Natalie Barney^^ commented that that Brooks was seeking to explore a range of modern types of women, including a new post-war single woman who rejected motherhood for masculine attire and her own career – a highly controversial theme for the time.

^ Kenneth Silver, Esprit de Corps, The Art of the Parisian Avante-Garde and the First World War, 1914-1924, 1989

^^ Bridget Elliott, Deconsecrating Modernism: Allegories of Regeneration in Brooks and Picasso, in The Modern Woman Revisited: Paris Between the Wars, 2003

Suggested Videos and Reading

Review of a book about Puvis

http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn11/review-of-pierre-puvis-de-chavannes-by-aimee-brown-price

Puvis confessed he preferred "rather mournful aspects to all others, low skies, solitary plains, discreet in Hue".

Create your own artwork to express Hope and re-birth.

See if you can achieve a rhythm across the work, using a limited and sombre palette.

Are you able to create a sense of symbolism?

Jeanne Jacquemin

Most of her paintings can be easily identified by the sad figures – usually waif-like or gaunt women in anguished or dreamlike states – which appear to haunt her paintings. She mostly used subdued tones in her pastels which adds to their subtlety.

Daydream (or Reverie), left, appears to be typical of her work, with a solitary, somewhat melancholic or pensive, figure set in front of a landscape. Blues and purples feature in the background, as do the strawberry blonde hair and blue-green eyes, which are thought to be similar to the artist’s own features. Does the use of the garland of flowers suggest a Christ like quality? It was not unusual for her male Symbolist counterparts to explore the theme of the self as Christ, and Jacquemin may have also chosen to do so. The second image (La Douloureuse et Glorieuse Couronne) is certainly suggestive of this motif, with the crown of thorns and eyes raised to the heavens.

From 1892, together with other Symbolists and Post Impressionists, she participated in a series of Peintres Impressionnistes et Symbolistes exhibitions, which were held between 1891 and 1897.

The catalogues of these exhibitions show that Jacquemin was both well represented and well received by some of the most significant critics of the time. Rémy de Gourmont from the Mercure de France wrote that her “overall effect produces something that is full of the new” with traces of “dreaminess” in blue-green luminosities” and impressions of “androgynous figures left to float like the unhealthy, yet adorable haze of desire around those heads so infinitely tired of living“.

Gourmet compares the dreaminess in her work to fellow Symbolists Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, and her work is similar in style to Puvis de Chavannes. There is also an echo of Paul Gauguin in some of her works.

One critic, writer and poet Jean Lorrain, was particularly taken by Jacquemin’s art, that he felt might be used to mirror his own interests, which also included the occult. As a result, they collaborated on a short story, Conte de Noel. Written by Lorrain and accompanied by five lithographs by Jacquemin, it was published in 1894. Lorrain’s support for her during the 1890s may assisted in her public recognition. For example, in 1893, she was invited to represent France in the tenth Les XX exhibition in Brussels, where she showed five works. Unfortunately, the close relationship between the two deteriorated and her reputation suffered as a result.

As well as her paintings, Jacquemin also produced a number of charcoal drawings and prints (lithographs) which were not as widely exhibited.

Perhaps the best known is a colour lithograph, Saint Georges, c 1898, which appeared in L’Estampe Modern that year.

The description of print in the magazine read,

“This print represents the young and valiant knight of Cappadocia, sweet as a virgin but strong as a lion, who is described in the Golden Legend as fighting and killing the dragon who was preparing to devour the daughter of the King of Libya. Thus, this heroic character inspired the traditions of many peoples, and since the time of the Crusades he has been known as the patron saint of the armies”.

It has been said that many of her works are self portraits, and there is certainly a similarity in the facial structure in a several of the paintings and prints shown on this page. Even the Saint Georges lithograph appears, if not female, at least androgynous.

Not a great deal is known about Jeanne Jacquemin or her work from the late 1890’s onwards. After nursing Lauzet until his death in 1898, she married Lucien Pautrier, and perhaps she chose to no longer exhibit, or it may have been the acrimony between herself and Lorrain (including a very public law suit) and the death of Lauzet which resulted in her being hospitalised for a short time that led to her being less interested in art. She divorced Pautrier in 1921, and married occultist Paul Sédir later in the same year, suggesting that she maintained her interest in the occult throughout her life time.

Jacquemin is thought to have died in 1938.

Primary Source: Jeanne Jacquemin: A French Symbolist, Leslie Stewart Curtis, Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Autumn, 2000 – Winter, 2001), pp. 1+27-35

Jeanne Jacquemin (Marie-Jeanne Coffineau) was born in Paris in 1863 to Marie Emélie Boyer, and was adopted by Lord Juliette Boyer and Louise Coffineau in 1874. However, details of her upbringing are sketchy and conflicting, and it isn’t known what formal training she may have had in drawing, painting or print making.

In 1881 she married a naturalist illustrator (who was also an alcoholic), Edouard Jacquemin. After they separated Jeanne lived with engraver Auguste-Marie Lauzet in Sévres on the outskirts of Paris, from about 1893. Through both Jacquemin and Lauzet she met a number of artists (including Puvis de Chavannes) and poets and developed an interest in Symbolism and the occult.

She first became known as a writer, when from June 1890 onwards she wrote commentaries on a number of writers and painters of the time for Art et Critique – she was particularly interested in Symbolist and Decadent literature. Many of the themes and images that she referenced in her writing appeared later in her own pastels. (Approximately 40 of the works that she exhibited during her lifetime were pastels, and unfortunately few remain.)

Like many other Symbolists, Jacquemin saw a close correlation between literature, music and the visual arts. She responded to the poetic and mystic delights of the texts in her commentaries, saying that “her ear keeps the music of poems long after the reading“. She also wrote that “I see images [from the poems] mount before my eyes” and that she wanted to “try to fix some of her visions“.

James Ensor

James Ensor who was born in Ostend, Belgium, in 1860 had many lifelong obsessions: himself, the sea, light and death. These obsessions and his wicked sense of humour fueled a long career.

He studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels, immersing himself in Bosch and Rembrandt, as well as in modern realists such as Courbet and Manet. Goya and Turner - artists “obsessed with light and violence,” as he put it, became favourites.

He aligned himself with a circle of painters who were politically leftist — anti-imperial, anti-clerical, pro-worker — and aesthetically progressive. In 1883 they formed a group in Bruselles called Les Vingt, or the 20 (XX), and organized a salon that drew contemporary artists from across Europe, including Monet and Seurat.

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ensor exhibited in the salon for a decade, but he had a bitter parting of ways when several of its members converted to neo-Impressionism, while he continued along the Realist path.

After a few years in Brussels, Ensor moved back to Ostend, which he would never leave again for any extended period. He had many friends, and a long-term romantic attachment, but never married. His top-floor studio was over his mother's shop, and from there he could look down on narrow streets and see beach and sea, and a grand expanse of sky.

The space was cramped and encouraged up-close, detailed work and led him to develop a method for making large-scale drawings from pasted-together sheets of paper.

Ensor is often referred to as the 'painter of masks', but he made paintings, drawings and prints in a variety of sizes, styles and subjects - ranging from tradition to fantastical. He brought masks up from his mother's shop, along with old clothes, and improvised models from them. With reproductions of art he admired, along with his own pictures, on the walls, and a human skull perched on his easel, the sources for his work were in place.

All these sources began to coalesce in the painting called The Scandalized Masks from 1883, a stripped-down, bad-dream version of a family portrait. A man sits at a bare table in a bleak room, a wine bottle at hand. A woman enters brandishing what looks like a flute or a stick. Both figures wear big-nosed masks. He cowers; she stares through dark-tinted spectacles. It is a chilling, hilarious moment in a drama that is also a farce, a Punch-and-Judy skit scripted by Zola. Death, in the guise of an avenging grandmother, comes to claim an incautious tippler.

Around the same time Ensor was painting from nature: cloud-filled landscapes, or skyscapes, filled with the North Sea’s churning weather. But these too implied threatening stories. In a painting called Fireworks the night sky is a curtain of fire. In Adam and Eve Expelled From Paradise, 1887 the banishing angel explodes like a midair bomb.

A year later he would complete his grandest epic, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889. In this painting his titular, ironic subject, the haloed figure of Christ at centre, who is both alone and engulfed by a roisterous mob, is virtually hidden from view. It is considered a self-portrait and—along with the painter's red signature at right, the sanguine "XX" insignia at far left, and the painting's prospective date—suggests Ensor's intent to cast himself as the true prophet of the art to come. Even more emphatic was his rejection of Seurat's Pointillist technique and what he considered the painter's coldly impersonal forms.

Ensor was acutely sensitive to what he saw as a wholesale critical rejection of his art, impelled by a “viciousness beyond all known limits”. Much of his work from the late 1880s onward was a response to this perception, a statement of exultantly defiant martyrdom.

He depicted himself beheaded, dissected, nailed to the cross. In one tiny painting he becomes a pickled herring pulled apart by two grinning critic-skeletons. In an etching we see him urinating against a public wall on which is scrawled “Ensor est un fou” — “Ensor is a nut job.”

Stylistically, his paintings are characterised by harsh colours and thick layers of oil paint, sometimes applied with palette knives or spatulas.

source: MoMa

"The mask means to me: freshness of colour, sumptuous decoration, wild unexpected gestures, very shrill expressions, exquisite turbulence." James Ensor

You may wish to view details of Ensor at these sites:

http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2009/ensor/#/intro/

James Ensor, Ensor with Flowered Hat

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch is the painter of The Scream, which is one of the most recognisable works in the history of art.

Both a painter and printmaker, Munch grew up in a household periodically beset by life-threatening illnesses and premature deaths. His mother died of tuberculosis when Edvard was only five years old, and his older sister, Sophie, died of the disease at the age of 15.. A younger sister was diagnosed with mental illness at an early age. Of the five siblings only one, Andreas, ever married, only to die a few months after the wedding

These tragic events left a lifelong impression on the artist, and contributed to his eventual preoccupation with themes of anxiety, emotional suffering, and human vulnerability.

(They were all explained by Munch’s father, a Christian fundamentalist, as acts of divine punishment.)

Much of his work depicts life and death scenes, love and terror, and the feeling of loneliness. He intended that these often open-ended themes would function as symbols of universal significance.

His painting style included the use of contrasting lines, blocks of darker intense colour, sombre tones, exaggerated form and semi-abstraction, which all contributed to create an air of mystery.

In 1879, Munch began attending a technical college to study engineering, but left only a year, and in 1881 he enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design. Here he studied the old masters, attended courses in the painting of nudes, and was instructed for a time by Norway’s leading artist, Christian Krohg.

Munch's early works were influenced by French inspired Realism.

The Sick Child

Edvard Munch The Sick Child 1885-86 (original version) |  Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1886 |

|---|---|

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1895 (drypoint) |  Edvard Munch, the Sick Child, 1896 (lithograph) |

Edvard Munch The Sick Child 1907 |  Edvard Munch The Sick Child 1925 |

Munch began a series of new paintings in the mid 1880s which departed from this earlier style. One of these was The Sick Child, which he would finish in 1886.

The Sick Child depicted his feelings about the death of his sister nearly nine years earlier. Munch revisited this subject many times until 1925.

(His brother, Andreas, also died young in 1895.)

In this painting you can see how Munch sought to evoke the sense of impending loss and grief through the heavily textured and scrapped back surface.

In each version he has adopted a different technique evoke the emotion of the scene.

From 1889 (the year his father died) to 1892, Munch lived mainly in France, funded by State scholarships, and embarked on the most productive as well as the most troubled period of his artistic life.

While studying in Paris and in Nice in the south of France, he was influenced by the Impressionists’ fascination with light and by the growing Symbolist movement which inspired his own symbolic use of colour and simplification of form. He also saw the work of Gauguin and Van Gogh, whose Starry Night he paid tribute to in his own painting of the same name thirty years later.

These works had a liberating effect on Munch. “The camera cannot compete with a brush and canvas,” he wrote, “as long as it can’t be used in heaven and hell“.

Munch’s experimentation with different media and techniques was driven by his expressive needs and he explored the different effects he could achieve by reinterpreting the same theme in a different medium. As a printmaker Munch made drypoints, etchings and lithographs in the traditional manner. However, he developed his own unique technique for colour woodcuts.

Despite suffering from mental illness, Munch was spectacularly prolific, creating an astonishing 1,008 paintings, 4,443 drawings and 15,391 prints, as well as woodcuts, etchings, lithographs, lithographic stones, woodcut blocks, copperplates and photographs. (source: http://www.finearts360.com)

Frieze of Life

Munch developed the great themes of Angst, Love, Sex and Death during the 1890s – a project he called the Frieze of Life – and to which he returned at the end of his life.

It initially encompassed 22 works for a 1902 Berlin exhibition.

With paintings bearing such titles as Despair (1892), Melancholy (c.1892– 93), Anxiety (1894), Jealousy (1894–95) and The Scream (also known as The Cry) Munch’s mental state was fully exposed.

His style varied greatly in these paintings, depending on which emotion had taken hold of him at the time.

He said of The Scream, "I was walking along a path with two friends. The sun set. I felt a tinge of melancholy. Suddenly the sky became a bloody red. I stopped, leaned against the railing, dead tired [my friends looked at me and walked on] and I looked at the flaming clouds that hung like blood and a sword [over the fjord and city] over the blue-black fjord and city. My friends walked on. I stood there, trembling with fright. And I felt a loud, unending scream piercing nature".

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The exhibition was highly successful and Munch became more widely known within the art world. Subsequently, he found brief happiness in a life otherwise coloured by excessive drinking, family misfortune and mental distress. From about 1892 to 1908 Munch spent most of his time between Paris and Berlin.

During a stay in Paris he met a number of Symbolist poets, which resulted in him designing the sets of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt at the Theatre de l’Oeuvre (at the same time that his Frieze of Life was being exhibited at the de l’Art Nouveau). In 1906 he designed the sets for another of Ibsen’s productions, Ghosts.

In 1903-4 he exhibited in Paris where it is likely that he saw early Fauvist painting and may have found inspiration in them. When the Fauves held their own exhibit in 1906, Munch was invited and displayed his works with theirs.

As the 1900s began, his drinking spun out of control. In 1908, hearing voices and suffering from paralysis on one side, he collapsed and finally checked himself into a private sanatorium, where he drank less and improved his mental health.

In the spring of 1909 Munch moved to a country house in Ekely (near Oslo), Norway, where he lived in isolation and began painting landscapes. Munch painted right up to his death, often depicting his deteriorating condition and various physical maladies in his work.

Munch’s work, which showed so much raw emotion, greatly influenced German Expressionism in the early 20th century.

Suggested Reading

You may be interested in this excellent information document about Munch by the NGV:

http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/40973/ngv_edures_edvardmunch.pdf

http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/ngv_edures_edvardmunch.pdf

Suggested Videos

Munch (there are several in the series)

Odilon Redon

When the term ‘Symbolist’ became current as a description of the new art and literature in 1886, Redon was considered the major Symbolist artist.

A painter, lithographer, and etcher of considerable poetic sensitivity and imagination, his work developed along two divergent lines. His prints explore haunted, fantastic, often macabre themes and foreshadowed the Surrealist and Dadaist movements. In about 1890 he turned to colour, producing vibrant dreamscapes in oil and pastel.

His interest was in the portrayal of imagination rather than visual perception.

His works were widely debated in Symbolist reviews in Belgium as well as France, but Redon himself was alarmed at the excesses of many of these interpretations and maintained a discreet distance from such groups.

His chief literary ally was Mallarmé, whom he met in 1883. Their friendship was close, although their only attempt at collaboration, Redon’s lithographs (1898) for Mallarmé’s Un Coup de dés, was not completed. (Redon has been termed ‘the Mallarmé of painting’.)

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Odilon Redon spent much of his childhood at Peyrelebade in France, which became a basic source of inspiration for all his art, providing him with both subjects and a stimulus for his fantasies.

He settled in Paris in 1870. There he befriended artist Rodolphe Bresdin, the epitome for the Bohemian lifestyle, who introduced him to the etching process and further sparked his interest in Delacroix and Symbolist writers. Redon was so influenced by Bresdin that he didn't use colour in his work for some time and instead worked in black and white. Of his preference for working in black and white he stated, “black is the essential colour of all things,” and “colour is too capable of conveying emotion.”

Redon learnt lithography from Henri Fantin-Latour and discovered that the unique qualities of this technique enabled him to achieve infinite gradations of tone, fine-line drawing, and rich depictions of light and dark. Also, through the possibility of editioning, he found a vehicle for broadly distributing the intimate imagery of his drawings.

He was profoundly concerned with the effects of light. Redon drew on varied sources, from Francisco Goya and Edgar Allen Poe to Darwinian theory for his mysterious, disturbing, and often melancholy Noirs series, works done exclusively in black tones—lithography, etching, and drawing

In 1884 he took part in the Salon des Indépendants, of which he was one of the founders, and in the Salon of the XX in Brussels (in 1886, 1887 and 1890).

He introduced pastels and colour in his work in the 1890s, making equally visionary, evocative works, stunningly ablaze in unnatural jewel tones. His finest creations are considered to be those in which his supple draughtsmanship and rare, phosphorescent colours evoke a mythical universe. His evocative images, whose sumptuous line encloses dream-like colours, attracted the praise of the Symbolist writers and admiration from painters as various as Gauguin, Emile Bernard, and Matisse.

Redon's work represents an exploration of his internal feelings and psyche. He himself wanted to "place the visible at the service of the invisible" so, although his work seems filled with strange beings and grotesque dichotomies, his aim was to represent pictorially the ghosts of his own mind.

Redon produced nearly 200 prints, beginning in 1879 with the lithographs collectively titled In The Dream. He completed another series (1882) dedicated to Edgar Allan Poe, whose poems had been translated into French with great success by Mallarmé and Charles Baudelaire. Rather than illustrating Poe, Redon’s lithographs are poems in visual terms, themselves evoking the poet’s world of private torment. There is an evident link to Goya in Redon’s imagery of winged demons and menacing shapes, and one of his series was the Homage to Goya (1885).

About the time of the print series The Apocalypse of St. John (1889), Redon began devoting himself to painting and colour drawing—sensitive floral studies, and heads that appear to be dreaming or lost in reverie. He developed a unique palette of powdery and pungent hues. Although there is a relationship between his work and that of the Impressionist painters, he opposed both Impressionism and Realism as wholly perceptual.

Henri Rousseau

Henri Rousseau used an overlay of popular and artistic sources and combined strong imagination to bring to life exotic locales and dreamlike states. His pictures were constructed using simplified forms, bold stylization, and incongruous but poetic juxtapositions. He was an untrained artist, and as a result didn't develop strong relationships with other artists painting at that time.

He worked as a gatekeeper in Paris but painted in his free time and made sketches from other artists’ work when he visited museums in Paris. He never left Paris, but gave the impression that he had travelled to foreign places and said that he had served in the military in the jungles of Mexico. When he painted such exotic subjects, such as The Sleeping Gypsy, he worked from his observations at les Jardins de Paris or the zoo, or from other artists' paintings.

Artists in the early 20th century admired Rousseau for his 'innocent' eye. Pablo Picasso discovered his work at a pawn shop in Paris and celebrated his work with a party. Rousseau's dreamlike paintings are an important precursor for the Surrealists in Paris in the 1920s and ‘30s.

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Surprised! (or Tiger in a Tropical Storm) was painted by Henri Rousseau in 1891. It was the first of the jungle paintings for which the artist is chiefly known. It shows a tiger, illuminated by a flash of lightning, preparing to pounce on its prey in the midst of a raging gale.

Unable to have a painting accepted by the jury of the Academie de Peinture et de Sculpture, Rousseau exhibited the painting under the title Surpris!, at the Salon des Indépendants where it received mixed reviews.

Rousseau had been a late developer (his first known work, Landscape with a Windmill, was not produced until he was 35) and his work is marked by a naïveté of composition that belies its technical complexity. Most critics mocked Rousseau's work as childish, but Félix Vallotton, a young Swiss painter who was later to be an important figure in the development of the modern woodcut, said of it: "His tiger surprising its prey is a 'must-see'; it's the alpha and omega of painting and so disconcerting that, before so much competency and childish naïveté, the most deeply rooted convictions are held up and questioned".

Rousseau's tiger is derived from a motif found in the drawings and paintings of Eugène Delacroix.

The fin de siècle (end of the Century) French populace was captivated by exotic and dangerous subjects, such as the perceived savagery of animals and peoples of distant lands. Tigers on the prowl had been the subject of an exhibition at the 1885 École des Beaux-Arts. Emmanuel Frémiet's famous sculpture of 1887 depicting a gorilla carrying a woman exuded more savagery than anything in Rousseau's canvases, yet was found acceptable as art; Rosseau's poor immediate reception therefore seems the result of his style and not his subject matter.

The tiger's prey is beyond the edge of the canvas, so is it left to the imagination of the viewer to decide what the outcome will be, although Rousseau's original title Surprised! suggests the tiger has the upper hand. Rousseau later stated that the tiger was about to pounce on a group of explorers. Despite their apparent simplicity, Rousseau's jungle paintings were built up meticulously in layers, using a large number of green shades to capture the lush exuberance of the jungle. He also devised his own method for depicting the lashing rain by trailing strands of silver paint diagonally across the canvas, a technique inspired by the satin-like finishes of the paintings of William-Adolphe Bouguereau.

Although Tiger in a Tropical Storm brought him his first recognition, and he continued to exhibit his work annually at the Salon des Indépendants, Rousseau did not return to the jungle theme for another seven years, with the exhibition of Struggle for Life (now lost) at the 1898 Salon. Responses to his work were little changed. Following this exhibition, one critic wrote, "Rousseau continues to express his visions on canvas in implausible jungles... grown from the depths of a lake of absinthe, he shows us the bloody battles of animals escaped from the wooden-horse-maker". Another five years passed before the next jungle scene, Scouts Attacked by a Tiger (1904). The tiger appears in at least three more of his paintings: Tiger Hunt (c. 1895), in which humans are the predators; Jungle with Buffalo Attacked by a Tiger (1908); and Fight Between a Tiger and a Buffalo (1908).

Henri Rousseau's work continued to be derided by the critics up to and after his death in 1910, but he won a following among his contemporaries: Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Paul Klee were all admirers of his work. Around 1908, the art dealer Ambroise Vollard purchased Surprised! and two other works from Rousseau, who had offered them at a rate considerably higher than the 190 francs he finally received. source: Wikipedia

Suggested Videos and Reading

It is thought that Klimt and his companion Emilie Flöge modeled for the work but there is no evidence or record to prove this. Others suggest the female was the model known as 'Red Hilda' as she bears strong resemblance to the model in his Woman with Feather Boa, Goldfish and Danaë. Klimt's use of gold was inspired by a trip he had made to Italy in 1903. When he visited Ravenna he saw the Byzantine mosaics in the Church of San Vitale. For Klimt the flatness of the mosaics and their lack of perspective and depth only enhanced their golden brilliance, and he started to make unprecedented use of gold and silver leaf in his own work.

The Kiss (Lovers) was painted by the Austrian Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt between 1908 and 1909, the highpoint of his "Golden Period", when he painted a number of works in a similar gilded style.

A perfect square, the work is composed of oil paint with applied layers of gold leaf, an aspect that gives it its strikingly modern, yet evocative appearance. It is considered Klimt's most popular work and captures a decadence conveyed by opulent and sensuous images. The use of gold leaf recalls medieval "gold-ground" paintings andilluminated manuscripts, and earlier mosaics, and the spiral patterns in the clothes recall Bronze Age art and the decorative tendrils seen in Western art since before classical times.

The two figures are situated at the edge of a patch of flowery meadow. The man wears a robe with black and white rectangles irregularly placed on gold leaf decorated with spirals. He wears a crown of vines while the woman is shown in a tight-fitting dress with flower-like round or oval motifs on a background of parallel wavy lines.

Her hair is sprinkled with flowers and is worn in a fashionable upsweep; it forms a halo-like circle that highlights her face, and is continued under her chin by what seems to be a necklace of flowers. The man's head ends very close to the top of the canvas, which reflects the influence of Japanese prints, as does the very simplified composition.

Gustave Klimt - The Kiss

Choose either a person or an animal as a subject and create a symbolist work. What techniques have you used to create a sense of mood or mythology?